In 50 years, the shark and ray population has halved

Indiscriminate overfishing has reduced the population of sharks, rays and chimaera by 50% compared to 1970 and this is leading to a loss of key ecological functions in marine ecosystems

Indiscriminate overfishing has reduced the population of sharks, rays and chimaera by 50% compared to 1970 and this is leading to a loss of key ecological functions in marine ecosystems

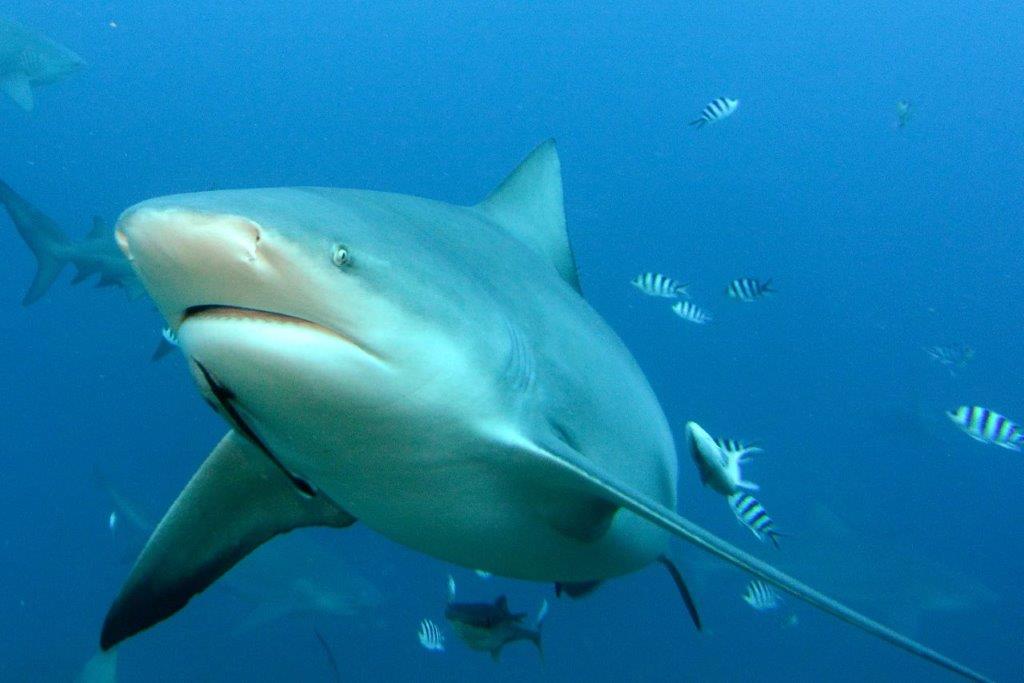

A new study has discovered that indiscriminate overfishing has led to a 50% reduction in the populations of sharks, rays and chimaera compared to 1970, and that this drop is leading to a loss of key ecological functions in marine ecosystems. Cartilaginous fishes or chondrichthyes are ancient animals and very widespread, with approximately 1200 different species catalogued. They can be found in almost all marine environments but are increasingly threatened by human activities, from pollution to climate change, so much so that it is estimated that, today, nearly half the species are at risk of extinction.

“Thanks largely to Hollywood portrayals, many people view sharks as a dangerous threat or a tough, voracious predator. Sharks and other elasmobranchs in fact fill many different niches and play important ecological roles across ecosystems. Furthermore, although they are tough in many ways, they have mostly not been able to hold up to intense pressure from humans”; this is the presentation of the study, “Ecological erosion and expanding extinction risk of sharks and rays” by Nicholas K. Duvaly, published on science.org.

This study sourced data from the Red List Index. The Red List Index (RLI) is based on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species assessments and is widely used to report on the status of terrestrial biodiversity and the effectiveness of conservation actions. Unfortunately, there is no equivalent for the oceans, where marinelife is often hidden and difficult to analyse.

“By developing a 50-year RLI of sharks and rays,” – notes the study – “we have shown how extinction risk has expanded across geographic, bathymetric, and biodiversity axes. Finally, we identified ecological, fisheries, and socioeconomic drivers of extinction risk based on RLI.” This serial depletion began in rivers, estuaries, and nearshore coastal waters before expanding out across the oceans and then down into the deep sea, and is greater in countries with higher fishing pressure and with larger contributions of harmful fisheries subsidies.

The decline in chondrichthyes as predatory fishes has significant consequences for other speicies in a wide range of aquatic ecosystems. The study noted that overfishing the larger species could eliminate up to 22% of the ecological functions necessary to support life in a determined environment. Sharks, rays and chimaera are not brainless predators, but play a fundamental role in the conservation of marine habitats: without them life underwater would never be the same.

“Sharks and rays – notes Dr. Nathan Pacoureau from the European Institute for Marine Studies at the University of Brest – (France) – are important predators and their decline is disturbing the food chain throughout the oceans. The largest and most widespread species connect the ecosystems. For example barrier reef sharks are fundamental in transferring nutrients from the deeper waters to the coral reefs, contributing to supporting those ecosystems.”

Although the decline in shark, ray and chimaera populations are worrying at an international level, the team that conducted the study also noted signs of progress. While for many years, thanks to their bad reputation deriving from the film industry, sharks were considered dangerous to people and therefore legitimate targets for hunting, or simply as a source of food considered to be aphrodisiac (fins), now a large amount of studies proving the contrary have begun debunking those myths.

In addition, starting from the 1990s shark and ray conservation has been increasingly recognised by regional and fishing bodies and by international agreements for wildlife, in particular through the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) A change in mentality, new regulations and a common awareness for the protection of our planet could make a difference and lead to a change that will bear positive results.

By Paolo Ponga

Topics: sharks