The sad story of the Cristoforo Colombo sailing ship: what happened to the twin of the Amerigo Vespucci

The ship was given to the USSR as war compensation, dismasted and reduced to hauling wood

The sad story of the Cristoforo Colombo sailing ship: what happened to the twin of the Amerigo Vespucci

The ship was given to the USSR as war compensation, dismasted and reduced to hauling wood

If you ask a sailor what the most beautiful ship in the world is, it is likely that he will reply: “The Amerigo Vespucci,” the famous teaching vessel belonging to the Italian Marina. There are very few, however, who remember that the spectacular ship had a twin: a ship just as beautiful as the Vespucci, but with a very different destiny. The name of this ship was the “Cristoforo Colombo”.

Both vessels were designed in the 1920s by lieutenant colonel Francesco Rotundi from Genio Navale, who was inspired by the ship, Monarca, the flagship of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. Built in the “Regi Cantieri” in Castellammare di Stabia, the twins were launched a short time from each other, in 1928, a began service in the Teaching Ships Division, with the purpose of training cadets of the Savoy Regia Marina Militare.

The teaching ship, Cristoforo Colombo with sails unfurled

The two vessels, although they were considered twins, had a few slight differences. They had the same displacement, 4146 tonnes, the same gross tonnage, 3410 tsl, only half a metre of difference in overall length: the Amerigo’s 101 metres against the 100 and a half of the Cristoforo. A difference probably due to the different inclination of the bowsprit which was caused by a different attachment of the shrouds, along the gunwale for the Vespucci, to the outside for the Colombo.

Another detail that distinguished the two were the two hawspipes cut on the loof from which the Colombo ran the anchor, while the Vespucci only had one. The biggest difference, however, was under the water. The Colombo was driven by two propellers, the Vespucci only had one. For everything else, the two sailing ships were indistinguishable. Even in their painting. Both had that characteristic white stripe on their sides, marking the gun deck from where canons were fired on sailing ships of the Eighteenth century.

Two vessels that were practically the same but which were destined to travel along two completely different paths, one to fame and the other to oblivion. It was at the end of the Second World War that the twin vessels were separated. At the table during the Paris Peace Accords, indeed, the Italians realised that their idea of invading Russia, losing a number of battalions of Alpini, was not one of their best. The Soviet Union demanded from the country the delivery of a dozen military vessels, including the Cristoforo Colombo, as war compensation.

The transfer of the impressive sailing ship stirred up a lot of resentment in the country. The Colombo, like her twin, Vespucci, was considered to be one of the mothers of all Italian cadets who learned how to sail on her decks, to then become real sailors. A few days before the transfer, some former exponents of the Repubblica Sociale were arrested for being in possession of a suitcase full of TNT which they were going to use to sink the ship, to save her the dishonour of being given to a foreign country that, even more importantly, they considered to be the birthplace of Communism. They didn’t consider the fact that if their plan had worked, Italy would have been forced to deliver the Vespucci instead.

And so, on 9 February 1949, the Cristoforo Colombo left Taranto for the port of Odessa, under the command of Captain Serafino Rittore. It is said that the night before departure, an unknown student of the training ship stole the painting depicting the landing of Christopher Columbus that decorated the the main room of the ship, and that now that same painting is hanging in the same room of the Amerigo Vespucci.

The ship arrived in Odessa on 2 March of the same year. In Augusta, where the vessel had stopped, Captain Rittore furled, for the last time, the Italian flag. Having taken possession of the ship, the Soviets changed its name to Danubio and repainted the hull in a sad military grey colour. For the following ten years, the sailing ship was used as a training ship for the USSR Navy, but without enthusiasm and very rarely. The subjects and training of Soviet cadets did not include sailing courses, and soon they realised that the Danubio was not useful for them and stopped taking care of her.

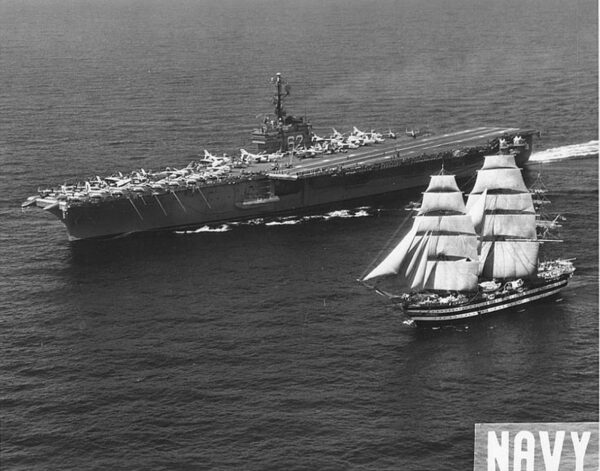

In 1961 it was already clear that the vessel was in need of some serious maintenance work but nobody took on the job. While the Amerigo Vespucci sailed across the oceans of the world and, when crossing the path of the USS Independence air carrier, it was hailed as the “most beautiful ship in the world,” her unlucky twin was being dismasted and turned into a motor cargo vessel for the commercial transport of wood.

In 1963 a fire broke out on board, destroying the hull, and making it economically infeasible to try and repair it. The Danubio was then abandoned and removed from the register of mercantile vessels. For another eight years it was moored in the port of Odessa as a floating wreck, until, in 1971, it was, mercifully, dragged to a shipyard and demolished.

In 1962, while the Colombo was being dismasted to be used for the transport of wood, the Vespucci met the air carrier, Independence. The training ship identified itself, “We are the Amerigo Vespucci”. “We know – answered the Americans – you are the most beautiful vessel in the world.”

Photography source: www.sandroferuglio.com, Wikipedia and US Navy

Topics: amerigo vespucci, cristoforo colombo, the most beautiful ship in the world