Understanding Weather Models

For long-term weather forecasting, the only way is to consult mathematical models, complex calculation programs describing the evolution of various physical parameters in the atmosphere and oceans for a determined number of days

Understanding Weather Models

For long-term weather forecasting, the only way is to consult mathematical models, complex calculation programs describing the evolution of various physical parameters in the atmosphere and oceans for a determined number of days

In the previous article we read about nowcasting, the very short-term forecast (2-3 hours maximum) which is based on careful personal observation and on the analysis of observed data.

For a longer-term weather forecast the only tool is the use of mathematical models, complex calculation programs that describe the evolution of the various physical parameters of the atmosphere and oceans up to a certain number of days (NWP numerical weather prediction).

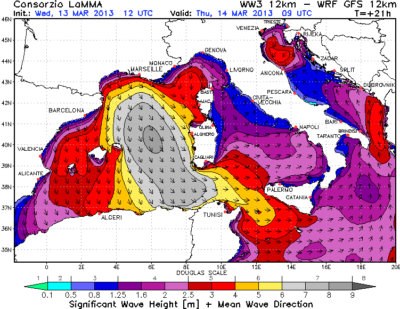

Significant Wave Height – Courtesy LAMMA

Any kind of bulletin, such as Meteomar on Ch 68, is the result of a careful analysis of the models by meteorologists – their experience and knowledge are crucial in correctly interpreting the output of the computers to draft the forecast.

Anybody can consult the best models, by computer or smartphone, however the considerable amount of information today can sometimes confuse us, making our decisions more difficult instead of facilitating them.

Hence the need to know weather models, to make a critical analysis of the weather information that we find on the net and not get lost down the internet rabbit hole.

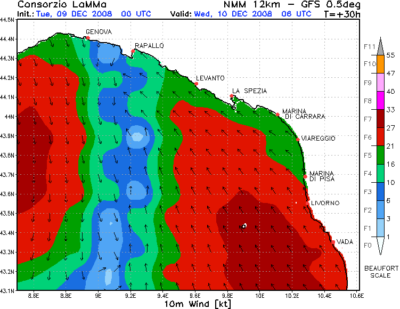

Wind Detail – Courtesy LAMMA

The production of the numerical forecast is divided into three phases:

- the collection of observations for the determination of the initial state,

- the “picture” of the atmosphere before the forecast,

- the forecast with the numerical model,

- the verification of the forecast.

The initial atmospheric state is determined over the entire globe with the help of meteorological stations, sounding balloons, observations by ships, planes and satellites.

Observations do not uniformly cover the entire globe, for example most of the seas remain uncovered: this uncertainty propagates within the numerical model and is one of the causes of errors in weather forecasting.

Using forecasts based on a set of models (ensemble forecasts) helps

reduce forecast uncertainty and extend the weather forecast further into the future than would otherwise be possible with the results of a single model.

Meteorological models are divided into two broad categories based on their spatial resolution: GCMs and LAMs.

GCMs (Global Circulation Models) are general circulation models, they are able to simulate atmospheric evolution over the entire globe, up to the stratosphere, and especially for long time ranges (384h = 16 days).

The most reliable general circulation models are the European ECMWF and the American GFS. They are also the most easily accessible online and can be consulted on many sites:

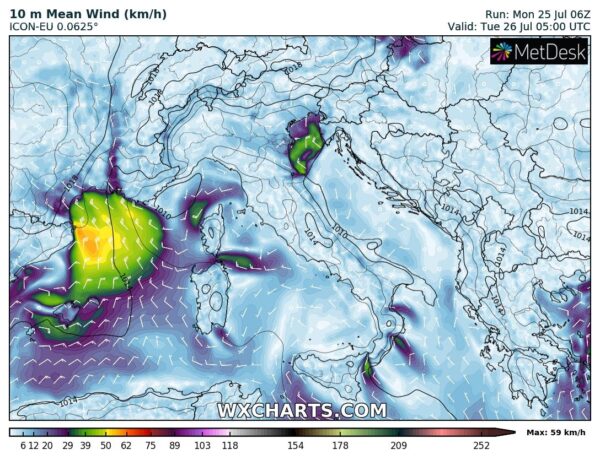

Example of GFS (Wetterzentrale)

Example of ECMWF (Wetterzentrale)

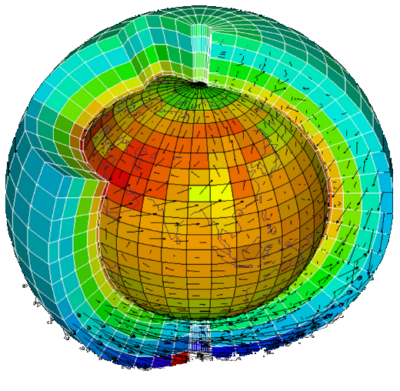

Forecast Grid – Courtesy of NOAA

LAMs are limited area models: they simulate atmospheric evolution over smaller areas, with increasing detail but for shorter time ranges (48-120h = 5 days).

LAMs are directly dependent on the GCMs, in fact LAMs, in addition to initial conditions, also need the conditions in the neighbouring areas which are provided by the superior model, in which they are nested.

To progressively increase the resolution there may be a succession of even three LAMs, each of which uses the data calculated from the previous one: the more precise the description of the physical phenomena is, the more the calculation difficulty increases, therefore inevitably the forecast time is shortened, only up to 48H in the models with maximum detail.

Furthermore, LAM models are divided into hydrostatic and non-hydrostatic models, with a profound difference in the forecast of precipitation, which is a field characterized by considerable unpredictability and which involves very small space-time scales.

Hydrostatic models with resolutions up to 6 km contain a description approximation of convective phenomena (storms, convective systems, squall lines), non-hydrostatic models are able to describe precipitation systems with greater precision and with a resolution of less than 6 km.

The most reliable LAM models for the Italian basins are the Lamma’s WRF and the CNR’s Bolam / Moloch

Example of Bolam model (Lamma)

Model Series – Courtesy of CNR

Alessandro Casarino – Navimeteo

Topics: navemeteo, weather models